The Social Files #14: Life is Short

a conversation with Harrison Pollock on sabbaticals and filling the gaps

As the world prepares for World War III (no joke), death has been on my mind. There’s a lot going on in the world. Protests, Trump’s trial, natural disasters. Doomsday aside, life’s fragility has hit close to home for me as well.

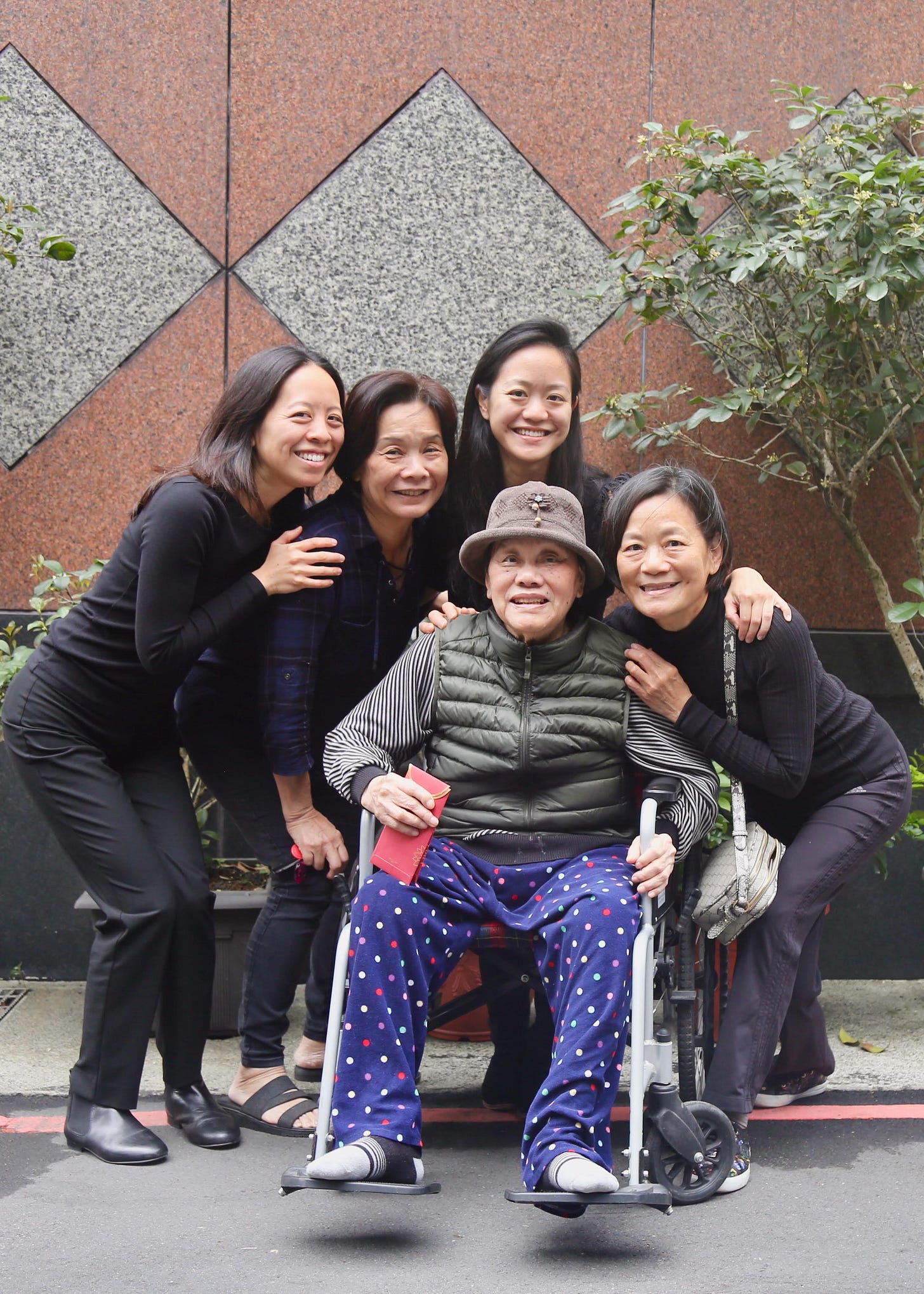

On the heels of my Grandpa’s passing, I flew to Taiwan for his funeral service in late February. During this trip, I also saw my Uncle one last time (before he too passed away) and reintroduced myself to my grandma with dementia. Life is so fragile. Its abruptness takes you by surprise every time. But I was not engulfed in a wave of grief like I expected.

Of course it’s sad when people, or our versions of them, die. One day they can be rising at 3am to swim in the ocean — the pinnacle of health — the next they barely know their own name. That's the story of my grandpa, who lived an active life until experiencing a steep decline in his final years.

Perhaps the greatest lesson from death is to double down on life itself. As we march toward our inevitable end, which we all are, we can be compelled to live with greater urgency now. You think you can always write that book, tell someone you love them, or travel the world — until the window closes unexpectedly.

My time in Taiwan ended up being a warm month-long reunion with many family members I hadn’t seen in a decade. Surrounded by a large and extensive network, I marveled at the abundance of connection found in the tight-knit fabric of a society that prioritizes cohesion. Growing up within a self-reliant nuclear unit in the US with my two hard-working parents and older sisters, I was never exposed to the bloodline “village” people speak of when they hearken to the days of living within shouting distance of cousins and aunties. While I value my independence and hard-wired routines, this is certainly something I’ll be thinking a lot about as I try to to build my own form of social support back here in the States.

This weekend, I'm excited to be running the Avenue of Giants half marathon up in the redwoods at Humboldt State Park. I'm also offering more free yoga outside my usual classes at CorePower, which I've been itching to do for a while. (If you're in the Bay Area this month and interested in joining, please message me for details!)

Life continues with its natural ebbs and flows but overall, I am so grateful to be riding on some momentum and harnessing the life-giving energy of those who came before me, my grandpa and uncle. In memoriam.

A Conversation with Harrison Pollock

Death might be an odd way to start today's conversation. But if life is short and fragile, why not take a sabbatical? See the world?

My friend (and former Stata TA in grad school!), Harrison Pollock, recently decided to take a year off from his job with the Canadian government. He just finished a stint with Global Affairs Canada, Canada’s version of the State Department, where he co-lead data operations to help over 850 Canadian citizens leave Gaza in the midst of the Hamas-Israel conflict. No big deal.

I wanted to understand what Harrison is hoping to get out of his sabbatical, or what he describes as "learning away from work", and whether he thinks this is something more people should consider.

Our conversation is broken up into two parts. The first sets the stage for why he’s embarking on this trip in the first place. The second was recorded a few weeks ago after he completed the first leg of his trip on an organic farm in Mexico through WWOOF. We caught up on some of his initial takeways as he got settled in to the next leg of his trip volunteering at an Indigenous organization in Oaxaca, Mexico.

Harrison is one of the most thoughtful, curious seekers of knowledge I know. Most people are content to live in their silos, or relax on their time off. Not Harrison — it’s evident in how intentional and humble he is about assessing and filling the gaps in his knowledge and experience bank. Life may be short, but there's certainly no shortage of things to learn from if you simply look around.

January 14, 2024

Conversation #1: Ottawa

LG: So how would you describe the next chapter you're about to embark on? Is it a sabbatical, a year off, a vacation?

HP: Well, I have to stop myself when I say I'm "leaving work" because I don't see it as leaving work. I see it as doing a different type of work and frankly, a work that I should have done before I started working. It will be very different from my current job. I think it will be harder in some ways, easier in other ways, perhaps more flexible.

I think for me it's mostly about being intentional in filling the gaps in my own experience and knowledge on many dimensions.

The plan is roughly: Spend six weeks working on a farm in Mexico, and then work several months with an Indigenous organization in Canada. (Note: Since this conversation took place, Harrison decided to work with an Indigenous organization in Oaxaca, Mexico instead.)

I also want to spend some time in rural Quebec. I speak good French, but I realized recently that language and culture are somewhat distinct. I have a strong grasp of the French language but less of a grasp of Quebecois culture. Recently there was a death of a famous Quebec singer and I'd heard of the guy before, but I wasn't really that in touch. I realized that I need to spend more time in rural Quebec, but also just with people who are Francophone for an extended period of time to get more connected on the cultural side because that's important for me.

So those are the three components of my trip and we'll see how it goes.

LG: It seems that in your "work away from work", you're looking to fill in the gaps of your knowledge through experience. Would you say they all tie back to professional and personal development in some way?

HP: I think partially. There are some professional gaps, but I do see this more as personal development. Many of us — many of our friends — do 95 percent of their work with a computer, sitting in an office of some sort and not being outside. That’s a biased view of the world because much of the Global South is involved in agriculture.

I know that you put a seed in soil with water and sun and in time, it turns into a vegetable. I'm not even sure if that's actually correct. Like maybe you don't need water in some cases. That's the extent of my knowledge of agriculture. Yet it is so fundamental, not only to human civilization, but to international development, which I am purportedly involved in. So to me, it's just a very basic gap in my own knowledge and experience. If I want to work in international development policy, I should probably know the first thing about the life of 80 percent of people in the Global South.

That's just one small example of a bias I don't want to have.

I want to think about work and life in a different way. Or rather, I want to have my defaults not just go to white collar office work when I think about what human beings do.

I know the facts, but I have not experienced that as much. I think that's important: to use your body, get outside, move around and understand a different way of work.

From a more professional perspective, as an international development professional, one shouldn't, nor can one, learn international development by living in Ottawa, Canada. I want to use my Spanish and my French. It's an unbelievable joy to be able to speak in other languages because not only does it work your brain, but you're able to connect with people on a different level. You're able to reach into cultural experiences and make connections that you couldn't make in English. It also humbles you. You're not as smart in other languages. You don't come off perfectly. In French, I'm almost 100 percent fluent. Spanish, I'm definitely not. But in both, there's still a sense of — ugh, I'm not saying exactly what I mean. I think that's an important place to put yourself in because whenever you talk with someone who doesn't speak English perfectly, that's how they feel too.

Professionally, if I'm going to stay in the Canadian government for some time, it behooves me to understand Indigenous people. Only recently has Canada been grappling with the horrific legacy that it's left, mostly in residential schools where Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their communities to be taught and "kill the Indian in the child", which led to a period of great removal into the foster care system. All of that is important to know professionally as someone in the Canadian public service. But even if I were to not return to the Canadian government, I think it’s important just to understand these realities and the mistrust that exists in government, to understand the harm that was caused, and to try to contribute in a positive way to alleviate that — even if as just one person I can do very little.

LG: Cost is top of mind when some people consider going on a sabbatical. One is the cost of whatever activity they want to do during that period of time, be it travel or taking a class etc. But there's also the opportunity cost of what they could be making during that period of time. When I took my sabbatical, I thought of it as an investment that wouldn't necessarily be great for my bank account but would pay dividends in terms of personal growth and edification. A year full of experiences, a year of stories. Think of all those great conversation starters.

HP: Well, that's not the main motivation.

LG: I know that's not the impetus for you. But what is it then?

HP: A few months ago I took one of those quizzes that asked about your close friends and their characteristics. For me, I was pretty diverse on friends with various racial, countries of origin, and gender identification but had horrific diversity on educational attainment. You go down the list of my friends: Master's, Master's, Master's, PhD, Master's, Bachelors.

I think about my sister who is one of the few people I'm close to who does not have a university degree. I learn a lot from her. I'm not radically different necessarily, but she carries such a different perspective on things.

LG: So, do you think we all have a responsibility to be more well-rounded or to fill gaps in our knowledge?

HP: I was telling this to some family members when they asked what I was going to do this year. They pushed back and said, essentially, don't apologize for who you are. You are a great person blah, blah, because I was going on about how I have all these gaps and I haven't worked on a farm or with my hands, I don't know people who aren't educated etc. And they were like, who cares? You were born in this way. You've lived your life like this. That's fine. Don’t apologize.

And I reject that view. You can quote me on that. But I do think that is a perspective many people would have, which is: we don't all have to be on some journey for self improvement. That shouldn't be a prerequisite of life.

April 18, 2024

Conversation #2: Oaxaca, Mexico

LG: Alright Harrison, tell me how the first leg of your trip was.

HP: Okay. The main takeaway: It's very complex to run a farm. Farm work combines physical work and intellectual work. You have to be extremely savvy, extremely knowledgeable. You have to be physical. You have to understand risk. You need to understand business. You need to understand nature, the climate, the soil. I mean, there’s so much you need to understand. You need to have connections. You need to know suppliers, you need to know prices, I mean, it's just one thing after another.

I was just really taken by how multi-layered it is. This was a five acre farm, not enormous, but not tiny either. There are two owners, a husband and wife, and one employee. Then another volunteer and I lived in a small house on the farm property.

LG: What kind of work were you doing?

HP: Mostly physical work, I had never done so much physical work before. It's boring and it's difficult. But that's what many people in the world do.

On the farm, the main crop was corn but there was also a lot else. There were avocado trees and different types of fruits. There was mint, chamomile, pigs, chickens. It really run the gamut of things.

I was amazed by how much they have. And of course, each of these different crops has a different watering schedule for a different climate for different types of plants. I was like, how do they keep it all in their mind?

LG: Did the farm use any tools or technology to keep track of things?

HP: I'm not sure. Well, one thing with organic farms is that you don't use pesticides or other chemicals and that all sounds great until you realize what those chemicals do. They do a lot of good stuff, like remove the weeds and the rats and the pests from killing the plants. So it's great that it's organic, but you're going to need a lot of cats and dogs to eat the rats. The farm's chickens… 150 of them died from a disease. I don't know what happened.

Then I was spending a lot of time de-weeding. You have a whole thing of weeds. I mean, you're taking the hoe, you're going in it, you're trying to take it out while at the same time not trying to kill the plant, which is right next to the weed. It's not an easy task. I did that for a few days for the mint plant and some other plants.

One of the farm owners told me that because there was so much less rain this year than last, there was 70 percent less corn. Yet even with that, it was more corn than I've seen in my entire life. I mean, there were like 50 20-kilo bags, big bags, all filled with corn. To me, it seemed like a lot. But he said last year there was three or four times more.

Anyway, the physical work was tough. It was also very hot. We didn’t eat during the day. So it's just breakfast, and then work six hours roughly, and then dinner. Some of these days were easier than others, some of them were really exhausting and I'd take frequent breaks. I wasn't pushing myself to the limit, but it was a good lesson in the not so glamorous side of things.

LG: So it was just five of you — you, the other volunteer, the one employee, and the farm owner couple — out in the fields working at any given time.

HP: Well, not even, because when you don't have running water, running a house is a full time job, so the woman owner would be washing the dishes, cleaning the house from the dirt etc. We had ready water access from… what's it called?

LG: A well?

HP: Hoses. I can't even imagine how much work it would be if you had to grab water from the well. Thank God, for laundry there was a washing machine, but no dryer.

Also, they cooked everything from almost scratch. Not 100% but probably the majority of the food was from the farm. Incredible food. The man was a chef before so you combine the skill that they had with the fresh ingredients, it was top notch Mexican cuisine. But on the downside, everything took a long time because they were starting from scratch. You're cleaning everything. So once you're done with one meal, you have to start preparing for the next.

Another interesting realization was just the idea of making your own food and having it ready. There's a sense of accomplishment to see the fruits of your labor. Our "knowledge work" sometimes yields very limited tangible results. But there is something to the fact that you produce this, you pick this, you grew this, there is something beautiful about that. At the same time, it's not glamorous. I sometimes felt like putting some food in the microwave to eat, but the owners were insistent on cooking every day.

It's a different cycle, a different rhythm of how you're thinking about life. The farmers were following natural cycles. They weren't going on vacation. They hardly left. They couldn't. The farm is their life. There are no days off. The day off was going to the market to sell the goods.

The last thing I would say that it was the first time in my life I was doing a job that I was not particularly good at. Normally you get a job because you're hired and someone thinks you're good at it. But this was an important mental shift.

Most people in the Global South are hired into jobs that they're just doing because they have to. They weren't chosen. They're not some special person that wowed the interviewer.

So that was an interesting experience to have where I couldn't show off any knowledge. I didn't have any great insight into the farm. It was humbling.

LG: Well, no moment like the present, Harrison. Cheers to your "work away from work". Should we sing Rent?

HP: No Day But Today.

LG: Yeah, I don't know it, you can sing it for me.

HP: Yeah, it goes, well, I forgot the whole song, but it's like,

No day… oh no. Is it no daylight? No daylight today? I forget the… it's actually a great, oh no, it's like the, there's only, uh, no day but today, no day. But today there's only, there's only this. No regrets or something like that.

Maybe not.

LG: I'm pulling it up.

There's only us, there's only this

Forget regret, or life is your's to miss

No other path, no other way

No day but today

‘Til next time, friends!

I love getting up at 3am to swim in the ocean. 😂 The pinnacle of health!